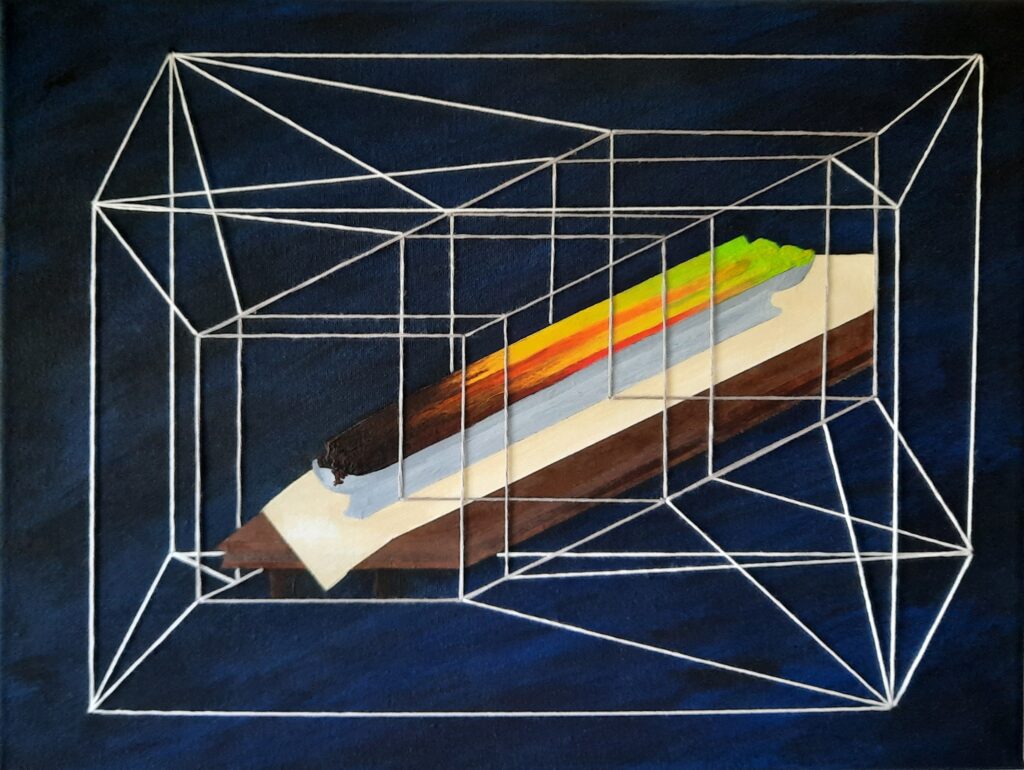

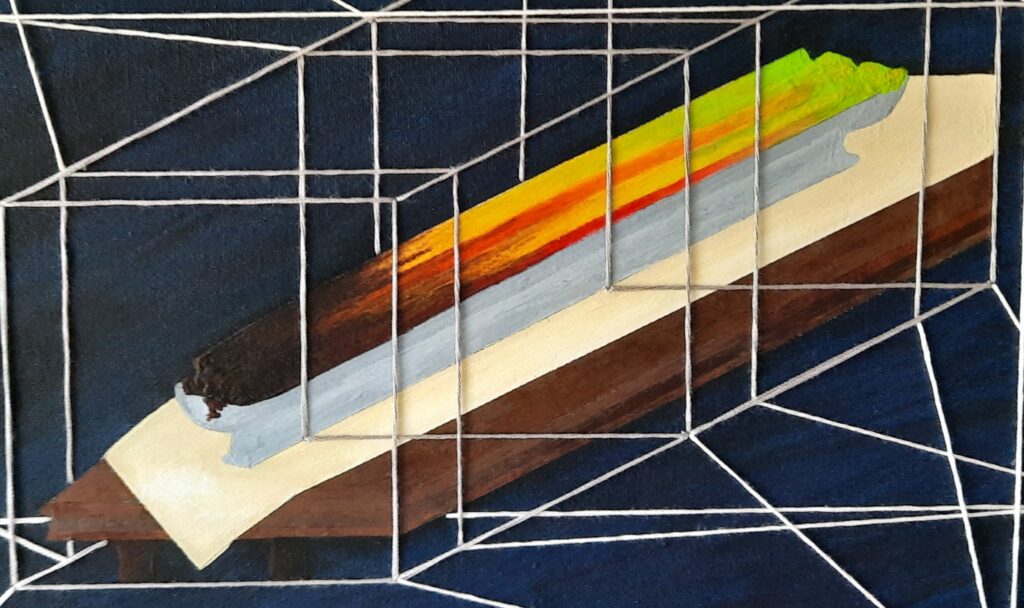

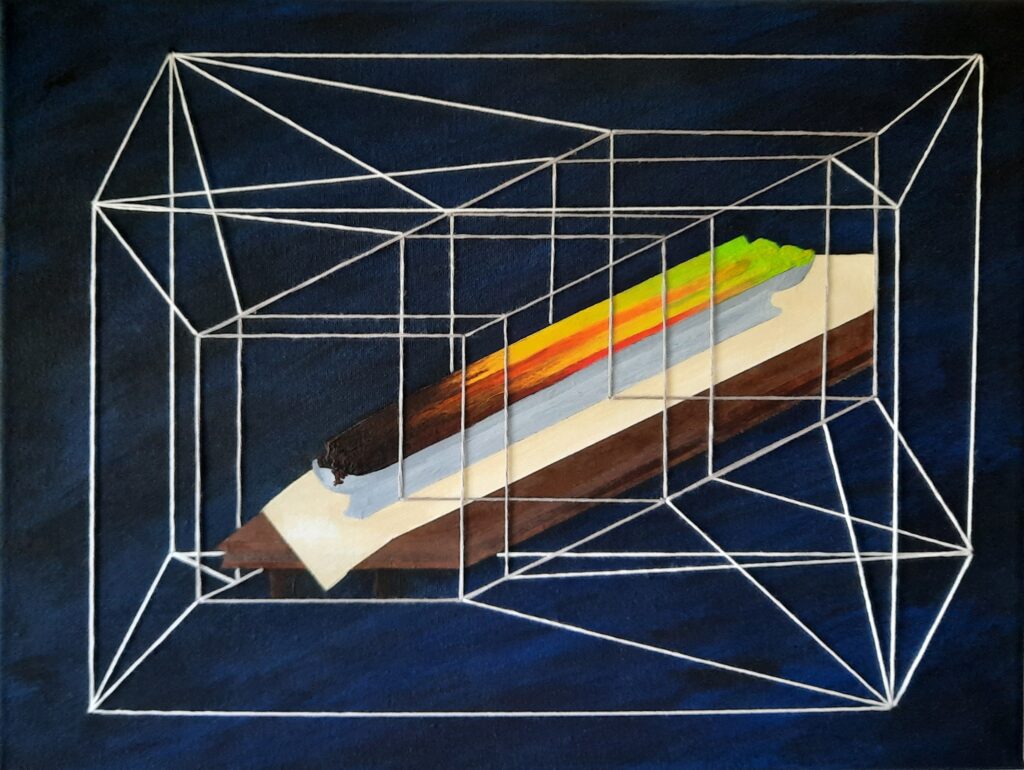

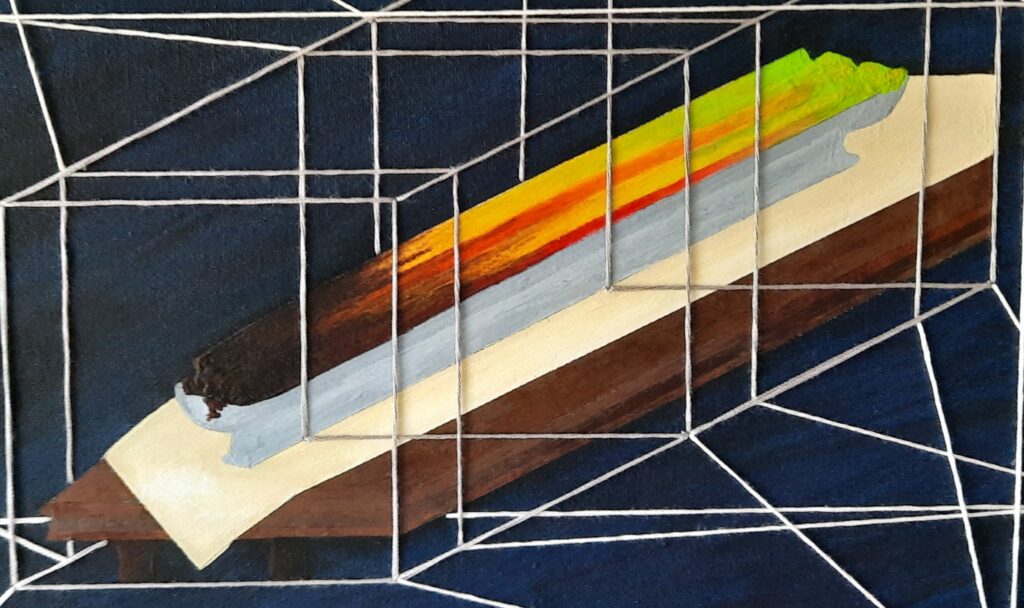

Still-life paintings from a new perspective: how does fruit ripen over time?

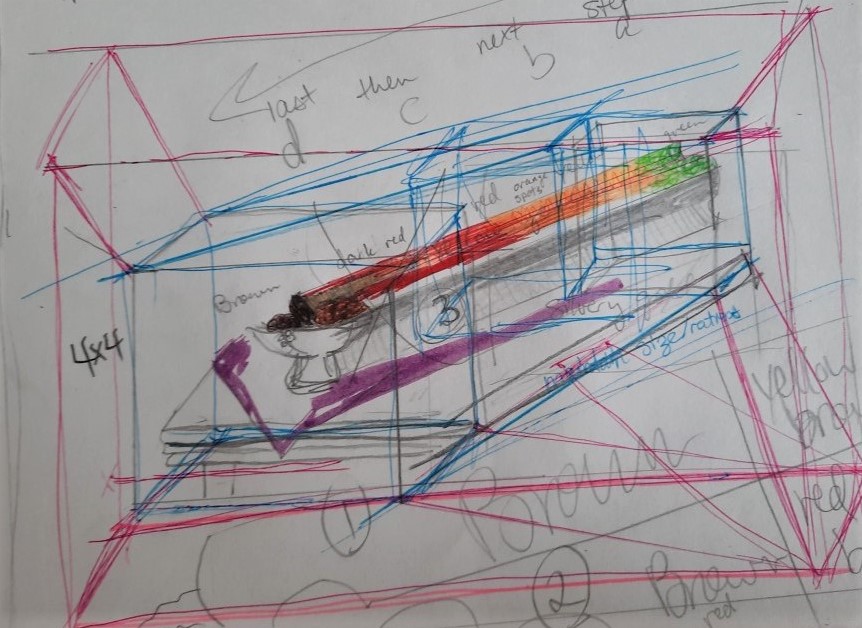

A depiction of a time lapse represented in 3 dimensions, from the perspective of 4 dimensions, on a mostly 2 dimensional plane.

Toward an empirical theory of consciousness for artificial intelligence

Still-life paintings from a new perspective: how does fruit ripen over time?

A depiction of a time lapse represented in 3 dimensions, from the perspective of 4 dimensions, on a mostly 2 dimensional plane.

Thanks to my partner, I am now interested in learning to paint. I used to like to draw but painting has always been a daunting task. There are so many parameters to worry about, like colour, strokes, light, proportionality; I think it overwhelmed me. From my perspective, drawing is a little simpler; you have lines and some shading if you’re good. I think the thing that I found the most daunting, however, was picking subject matter. Why do people draw or paint the things they do? Most of the time, I couldn’t think of anything to paint, and would always worry about how the final product would turn out. My fearful immature mind would think something like “if mediocrity is the enemy, then it’s probably best that I stick to what I’m good at.” How lame is that? So, it’s time to tackle the fear of colour-matching and start by just making a mess. That’s what toddlers do with paint, so that’s what I shall do too, but a little less literally because my sensorimotor cortex has a better grip on how to move my hand. It’s not a lot better, but it’s something.

The idea for what to paint came to me, luckily, one day as I was thinking about time and reading about Cézanne. I was thinking about all the versions of still-life fruits and flowers that exist in the world, and then realized that these images were a snapshot of the object’s life, and that at one point, that one apple might have been green rather than red, for example. What if one were to paint all of the snapshots of the apple? In that moment, my mind produced a weird multi-coloured snake inside a tesseract, and it was at that point that I knew I had to try to externalize this image.

With my limited skills in visual representation, I knew I would need to take this slowly and plan every step of the image-creation project. I know I will make mistakes, but planning ahead and determining the steps I need to take beforehand helps to reduce the impact of the errors on the final product. The dimensions were the first thing to plan out: how is this going to fit within the canvas? Next, it was making sure the components of the foreground were properly set in relation to each other. Now that I am working on colour and detail, the real challenge begins.

To take a representation from the mind’s eye and depict it with high fidelity on a piece of paper or canvas is the hardest step. This is made explicit in Derrida’s Memoirs of the Blind, and when I read segments of this book earlier in the year, it reminded me of the art I used to make as a kid and the feelings I had back then. That feeling of anxiety as the brain and body work together to represent a trait or idea (Derrida 36) is quite familiar, and perhaps it was this book that subconsciously rekindled my interest in creating visual art.Since skill is built up as the hand translates what the mind sees into line segments, angles, and shades of colour, I knew I would need a set “training-wheels” to get me going. By appealing to my experiences of drawing, I knew my pictures looked best when I could copy an image in front of me, as the external image is more concrete, visually, than my internal depiction. Existing still-life images act as my guide-dog as I feel around in the dark for ways of bringing this image to life. I know the vase needs to reflect light, but how? Fortunately, a quick internet search provides plenty of examples, but I am still looking for the right image, one that looks as close as possible to the scene in my imagination. I need to copy existing visual elements in order to articulate the ones produced by my neurons.

The lesson? More practice, less fretting. The expectations I place on my “art” are nothing but my own ideals, and after I challenge these ideals, the pleasure comes back. What ideals am I referring to? Productivity and achievement for the sake of bolstering one’s prospects or status, along with other notions that tend to suck the delight out of our endeavours. My partner often reminds me to enjoy the process and think less about the painting as a final product. Focus on the verb, not the noun. I am doing this for myself, not for the blog, not for my career, and certainly not for money. It’s an exercise in phenomenology, nothing more. Will thoughts of hustle-culture sneak up on me when I’m vulnerable? Yes, but that’s why this is about my inner representations, including those that make me doubt myself.

Works Cited

Derrida, Jacques, and Musée du Louvre. Memoirs of the blind: The self-portrait and other ruins. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

I wrote a rhetorical post a while ago that attempts to motivate a new perspective on qualia and why we ought to consider it as something philosophically valuable. My appeals to art and cultural products aim to be persuasive by connecting qualia to everyday experiences, however, I think it still comes across as too abstract or unclear because the arguments are not well articulated. One of my supervisors has been instrumental for pushing me to abstract away from the science and evidence, and I now have a general idea of where I went wrong in my previous attempts to clarify my own perspective. Emphasis on ‘general’ because there is a lot of work to be done before I fully understand the difference between where I was and where I want to go.

Qualia, ultimately, are just concepts, which essentially boil down to information. This information is applied to the lived experience of one’s own sense data, as received from the environment, either internally in the form of bodily feelings, for example, or externally, as generated by features of the physical world. When we notice this sense data, which I consider similar to phenomenal experiences or Chalmers’ registrations (Chalmers 214), we often need a way to conceptually organize it. As a functional system, the brain receives incoming signals and processes them through various functions or streams, subsequently creating perceptions from sensations (Wolfe et al. 3). Our perceptions, however, are malleable based on information the individual has access to. This ranges from subtle, unconscious shifts in perspective to deliberate thought processes aimed at rethinking the situation at hand. As the body turns data into information (Computer Hope) through functional biological processes, qualia serve to facilitate the mind as the body’s owner or central processing unit by providing additional information which structures and curtails the process of perceiving.

Qualia as information can be passed from human to human as expressions of subjectivity as a means of connecting with others, in addition to making sense of the world. If qualia seem to be illusory or unreal, perhaps it’s because the significance of this information is lost as we try to make sense of what the mind is really doing from a scientific perspective. It probably doesn’t help that ‘information’ is abstract, conceptual, and invisible, as its inherent subtlety enables one to easily overlook or neglect its importance for structuring human thought and behaviour. Perhaps we take our theory of mind for granted and ignore subtle forms of communication, deeming the exchange of knowing glances as something less significant than a well-formed linguistic phrase. Though the information expressed through these channels may not demonstrate a high degree of fidelity to the thought as it exists in the mind of the communicator, our mere ability to communicate this way suggests that additional information already exists in the mind of the receiver, information which can contribute to shaping of the act of perceiving data about body language.

Through qualia, we are better equipped to separate the signal from the noise to determine its meaning, however, we are also reminded through the sharing of these experiences via various mediums that even in our private subjectivity, we are not alone. The “what-it-feels-like” inherent in qualia may be unique to a particular body, but similarities may also exist between individuals. The knowledge of these similarities supports our endeavours to make sense of our feelings and sensations, ultimately allowing us to accept ourselves and our experiences as they are. Although the act of sharing personal, subjective experiences serves a practical social purpose like fostering cooperation and empathy, qualia are useful for individuals as well. The exploration of our subjective selves, along with some act of expression, also allows us to feel more comfortable as we process the deluge of sense data as received by various sensory organs within the human body. Through qualia, we are reminded that the body we inhabit is not a boundary between our inner selves and the subjectivity of others, but a structure that creates and presents information based on our experiences of incoming sense data. This information may be elusive, but it still exists and is significant for structuring human consciousness.

Works Cited

Chalmers, David J. The Conscious Mind: In search of a fundamental theory. Oxford university press, 1996.

Wolfe, Jeremy M., et al. Sensation & perception. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer, 2015.

In Quining Qualia, Dennett states “conscious experience has no properties that are special in any of the ways qualia have been supposed to be special” where qualia are considered “special properties, in some hard-to-define way.” His appeals to intuition aim to defend these ideas, however, the examples he provides may fail to convince the reader as objections can be drawn based on an understanding of nervous system functioning and through examining human behaviour. Here, I’m interested in providing an explanation for qualia which does not rely on some intrinsic property of the mind, but a product of culture which influences, and is influenced by, individual humans and their subjective experiences.

To be facetious for a moment, if qualia did not exist, how could one explain why it is that humans feel compelled to spend energy, time, and money on creating, sharing, and experiencing art? Dennett might appeal to the nature of subjective experiences or perhaps to our motivation for seeking pleasure, however there is much more to subjective experiences than one’s feelings or mental representations evoked by some stimulus. Knowledge surrounding a particular stimulus may shape the way it feels or appears from a first-person perspective; for example, mistaking a benign object for a threat of some kind. A coat and hat hanging on a wall hook inside a dark room may be mistaken for a person, perhaps causing one to feel threatened or startled by the apparent intruder, only to discover the truth after turning on the lights. The subjective experience prompted by the sight of the coat and hat is different than if the illusion had indeed been an unexpected guest, primarily due to the relief one is likely to feel at discovering the reality of the situation. In the case of experiencing art, subjective experiences may change over time or with repeated exposure, but our minds are also influenced by the minds of others. The ability to communicate our feelings to others introduces additional perspectives surrounding a particular stimuli, potentially altering one’s own perception and subsequent experiences. These shared ideas or experiences are then represented through cultural artifacts, practices, or beliefs, and aim to depict associations between sensations and perceptions. In this way, qualia are a features of the natural world insofar as they are a result of evolution and human intelligence, becoming “real” as they shape the ways individuals experience and interact with various stimuli.

Not all subjective experiences become qualia though, as some perceptions are more difficult to articulate than others. How to articulate one’s visual experiences of red? It may remind you of something, but it doesn’t necessarily feel like much to merely look at a red object. I can infer that you probably see the colour red like I do when I consider your behaviour around colourful objects. If someone were to indicate their inability to distinguish colours in the same way that I do, I might perform a quick test to verify the experiential discrepancy. Regardless of individual perception however, there is still “something it is like” to see the colour red as most of us do and are able to create representations appealing to this visual quality. Articulating the nature of ‘red’ on its own is rather tough because its qualities aren’t a composite of other visual qualities per say, at least not in the way that ‘orange’ is. From this perspective, qualia emerge through the act of communicating our experiences to others and through identifying the various phenomenological aspects they contain. Qualia feel real to humans because we use them to engage with artistic practices, almost like Dawkins’ memes but saturated in visceral associations to various sensations and perceptions.

If qualia aren’t real, then why does a collection of piano chords remind Debussy and other listeners of clouds? Language enables us to describe our subjective experiences using similes, where one environmental feature reminds us of something else. These associations are likely to follow certain regularities given the laws and constraints of our universe and our physiology, resulting in a similarities between subjective and shared experiences. I doubt any listener will associate Debussy’s pieces with the eruption of Krakatoa, but it seems reasonable to assume some individuals may think of water rather than the sky when listening to Nuages. Thus, it could be suggested that stimuli may evoke a potential set of qualia that humans may refer to when considering their own subjective experiences. Exactly which qualia are included and excluded is roughly determined by how a stimulus affects individuals as a result of their physiological functioning.

Qualia are products of human culture, not biology. The evolution of primates along with their tendency to socialize and enjoy participating in shared activities gave rise to a shared experiences and various ways to depict or describe them. Human cultures create classifications, distinctions, and ontological categories as way to explain natural phenomena and to share knowledge. This collective idea on how our subjective experiences appear to others facilitates bonding as humans learn they are able to relate to the private experiences of others.

Works Cited

Dennett, Daniel C. “Quining qualia.” Consciousness in modern science. Oxford University Press, 1988.

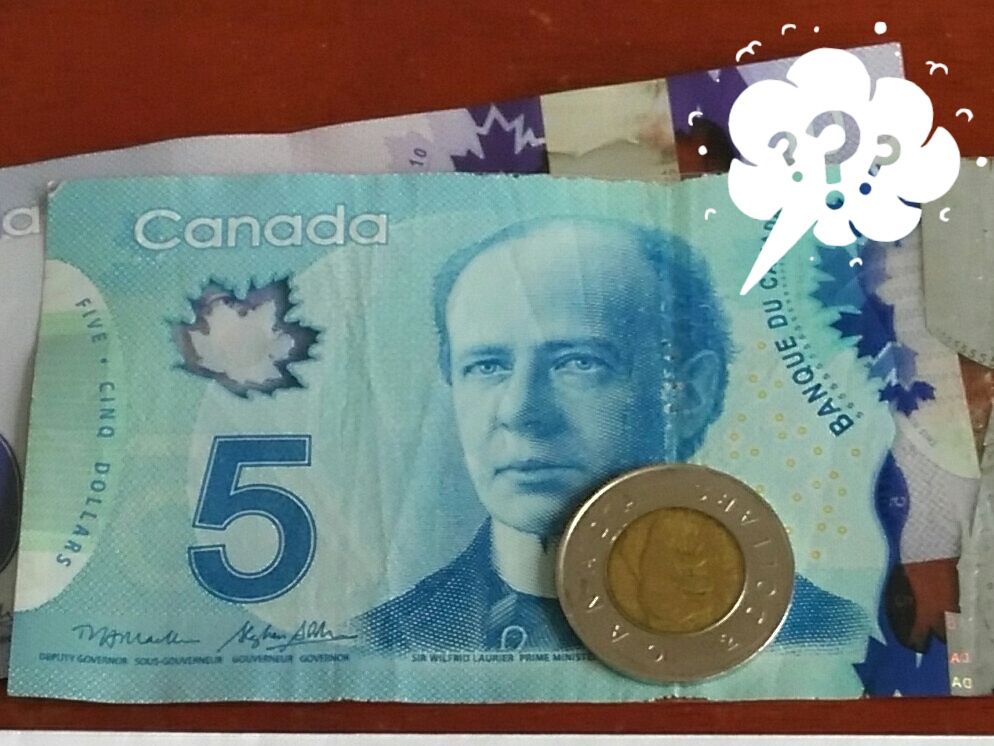

I came across this reddit post a couple years ago and thought it was quite funny. I can see Randall Munroe of xkcd comics drawing up a really good depiction of this imaginary phenomenon too.

“According to the multi-world theory, there is a universe where every flipped coin has landed on heads, completely by chance. Imagine rooms full of machines, just flipping coins with scientists baffled as to why it happens”

According to OP in the comments of the reddit post, this world “would have identical physics, [where] this just happens by chance” and “physics aren’t different in this universe, the incident with coins only landing on heads is pure probability, not a law.” I like to imagine that there would be individuals dedicating their entire research careers to this phenomenon, maybe pulling out their hair as no solid evidence is able to suggest why this happens.

If you, dear reader, felt inspired to fulfill my dream of depicting this scenario in an illustration of this scene, I would excitedly add it to the bottom of this post with full credit to you! Wilfred is tired and would like to retire; in this universe he studied the coin toss phenomenon in his free time.

Works Cited

While operational opacity generated by machine learning algorithms presents a wide range of problems for ethics and computer science (Burrell 10), one type in particular may be unavoidable due to the nature of complex processes. The physical underpinnings of functional systems may be difficult to understand because of the way data is stored and transmitted. Just as patterns of neural activity seem conceptually distant from first-person accounts of subjective experiences, the missing explanation for why or how a DCNN arrives at a particular decision may actually be a feature of the system rather than a bug. Systems capable of storing or processing large amounts of data may only be capable of doing so because of the way nested relationships are embedded in the structure. Furthermore, many of the human behaviours or capacities researchers are trying to understand and copy are both complex and emergent, making them difficult to fully trace back to the physical level of implementation. When we do, it often looks strange and quite chaotic. For example, molecular genetics suggests various combinations of nucleotides give rise to different types of cells and proteins, each with highly specialized and synergistic functions. Additionally, complex phenotypes like disease dispositions are typically the result of many interacting genotypic factors in conjunction with the presence of certain environmental variables. If it turns out to be the case that a degree of opacity is a necessary component of convoluted functionality, we may need to rethink our expectations of how ethics can inform the future of AI development.

Works Cited

Burrell, Jenna. “How the machine ‘thinks’: Understanding opacity in machine learning algorithms.” Big Data & Society 3.1 (2016).

John Worrall’s paper “Structural realism: The best of both worlds?” mostly outlines the debate occurring within the Philosophy of Science surrounding whether scientific realism or anti-realism best captures our intuitions and intentions regarding the scientific process and its history. Although this topic on its own is a fascinating discussion, it will not the focus of this article. Instead, I’d like to explore Worrall’s reply and its implications when approached from a metaphysical perspective. At the end of his paper, Worrall concludes that combining an aspect of realism with an anti-realist attitude produces a potential solution to the dilemma. Structural realism describes a perspective which can account for the predictive success of science while also explaining how scientific revolutions changed theories and research practices throughout history (Worrall 123). Structural realists believe that when scientific theories undergo conceptual change, their form or structure remains constant while the content of a theory may be modified based on new empirical findings (Worrall 117). He believes this account is able to explain how scientific theories are able to undergo both growth and replacement over time (Worrall 120).

However, structural realism can be further divided into two different categories which support differing views. The epistemic structural realist (ESR) believes all we can learn through scientific inquiry is the accuracy of a theory’s inherent structure, and not the concepts or entities themselves (Ladyman SEP). The more extreme version, ontic structural realism (OSR), states that there are no objects or things, and the universe is only comprised of structures, forms, and relations (Ladyman SEP). Van Fraassen describes this position as “radical structuralism” (van Fraassen 280) and appeals to science’s use of mathematical formulas to serve as motivation for this view (van Fraassen 304). Since physics uses math to describe how the physical world operates, and complex bodies of organic machinery operate based on the rules of physics, objects found in nature can theoretically be explained in mathematical terms. Although our conceptions of these entities may change dramatically over time, their mathematical descriptions and relations tend to expand as new discoveries are incorporated into existing theories (van Fraassen 305).

Although the discussion surrounding structural realism originally aimed to answer problems in the philosophy of science, OSR eventually became its own metaphysical view. This is partly due to discoveries made in physics over the previous century, shaping how we think about the natural world, especially in the subatomic domain (Ladyman SEP). At one point, an atom was thought to be the smallest unit of matter in the universe, with its original Greek word atomos meaning ‘indivisible’ (merriam-webster.com). Today however, we are able to run tests which not only divide atoms, but smash them together in order to inspect the pieces which make up the subatomic particles themselves. Furthermore, as our understanding of quantum physics grows, the less neat-and-tidy the world seems to be packaged.

My goal here is not to convince you to fully adopt the OSR perspective, but to consider it as a tool for drafting instances of artificial general intelligence and artificial consciousness. Personally, I find this approach to understanding reality very interesting and am compelled by the notion of “structures all the way down.” However, some may find this problematic as the relata seem to be missing. What is the ‘stuff’ that the structure is made out of? What exactly is being organized in a structural way? In a nutshell, segments of miniature structures. An example of this is the relationship between chemical bonds and the physical laws which binds them together. Or a Swiss army knife made of small metal parts, where these pieces consist entirely of a combination of metal atoms arranged into shapes. But these atoms themselves are just structures of subatomic particles, consisting of protons, neutrons, and electrons. Moreover, if we continue to zoom in, it turns out that these particles are just comprised of other particles arranged in different relations. Each contemporary understanding of “matter” and “mass” changes based on technological improvements, assisting in the production and interpretation scientific experiments. It may turn out that OSR becomes a useful perspective for conceptualizing our universe, especially as old assumptions are reworked to include new and possibly contradictory empirical discoveries.

Speaking of perception, if there are no objects, then does everything exist in the mind like Berekely thought? I think the answer to this is a little ‘yes’ and a little ‘no’: the brain creates representations of concepts which are based on learned regularities from interacting within an environment. From an evolutionary perspective, the brain adapted to help promote an individual’s survival by learning to recognize patterns and recall previous events. As neuronal structures developed to support new and more complex functions, the individual’s subjective awareness of their abilities grew as well, eventually producing mental concepts and linguistic labels. For example, neurons in the primary auditory cortex are arranged tonotopically, where particular cells responding to specific frequencies are arranged by pitch from low to high (Romani, Williamson, and Kaufman 1339). In this sense then, a C major scale played on a piano can be viewed as isomorphic to the way these frequencies are physically realized in the brain. Rather than the world or universe containing ‘a C major scale’, from an OSR perspective, reality only contains the laws which govern how sound pressures and vibrations must exist and operate such that a musical scale can be realized in a human brain. From an individual’s perspective however, this type of stimuli is represented as ‘music’ or ‘the sound of a piano’.

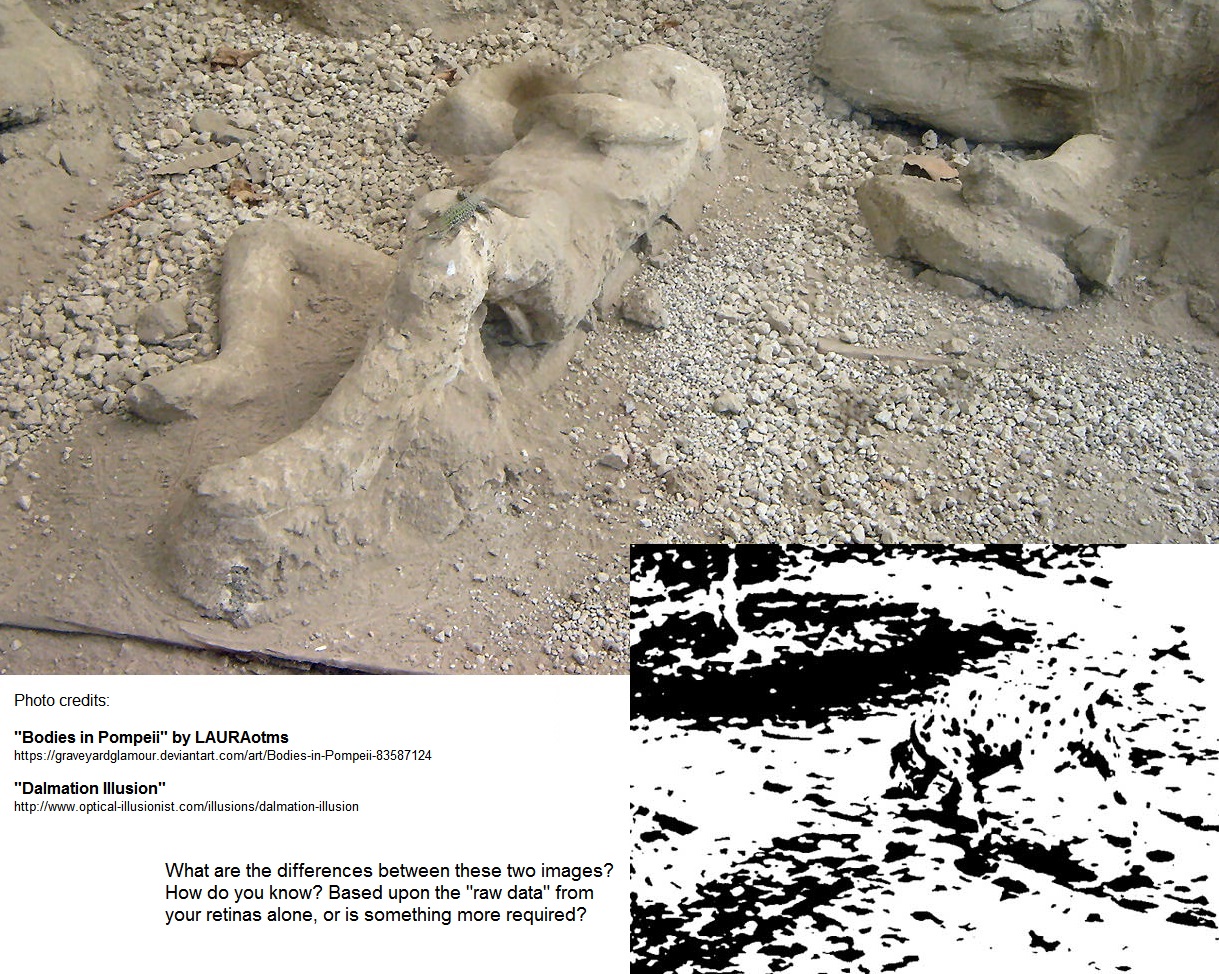

An unpublished article by Brian Cantwell Smith called Non-Conceptual World discusses a similar perspective to structural realism, claiming that concepts only exist in the mind (Cantwell Smith 8). One example Cantwell Smith mentions is the aftermath of the volcanic eruption which occurred in ancient Pompeii (see photo below). While he uses this as an example of how object recognition is an intentional process (Cantwell Smith 16), I was reminded of an optical illusion which shares important similarities to depictions of Pompeii. The Dalmation Illusion (see photo below) is just a series of black and white dots, yet somehow the brain manages to pick out the form of a dog. In reality however, there is no dog and the image is deemed an illusion. However, the image of the Pompeii disaster indicates that there really is a person amidst the variety of grey blotches. In both instances, the incoming visual information seems to be quite similar at first, but the stored contextual information associated with the visual stimuli creates a contrast in the conceptual representation of each “object”. I tend to agree with Cantwell Smith when he says “there aren’t any objects out there” (8) because an evolutionary perspective suggests the brain generated object-based concepts, not the universe.

If this is so, what can be said about human consciousness? Natural selection is the process of increasing genetic diversity through reproduction, as well as constraining it through environmental pressures, producing a mechanism for building and refining chemical and physiological structures. It seems likely that psychological structures are also subject to this same type of development, or at least impacted by it. Random genetic mutations may produce functional changes which impact neighbouring structures, requiring other neurons to update their internal and external organization as a result. If this change produces a large enough effect, a small patch of cortex or connected regions may also be impacted, leading the individual to notice alterations in their motor or perceptual abilities. By viewing the brain as a structure of networks and configurations, it can be suggested that consciousness may have emerged as a result of one or more self-organizing structures interacting within both internal and external environments over time.

Therefore, consciousness is an emergent property of the brain, but there may be more to this story, as will be discussed in future articles. Briefly though, consciousness, or some version of intelligent self-awareness, may be a direct result of the self-organizing system which constitutes evolution. Furthermore, could consciousness be an inevitable outcome of an instance of natural selection? Is there a threshold in the variables which makes this outcome necessity to occur, like an action potential in a neuron? I am also looking forward to discussing Dynamical Systems Theory and Information Theory as they relate to these ideas as well.

The reason OSR is important for designing artificial minds is because of its power to generate isomorphic versions of laws from the natural world. If an object or entity can be conceptualized as a series of structures with functional regularities, machine code and mathematical systems may be able to generate models which produce similar behaviours or results. Since neural networks and deep learning have found success in perceptual recognition, perhaps it will be beneficial for taking a developmental approach to artificial consciousness as well.

Edited version:

Works Cited

“Atom.” Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, n.d. Web. 26 May 2018.

Blauw, Laura. Bodies in Pompeii. 2008, digital photograph. https://lauraotms.deviantart.com/art/Bodies-in-Pompeii-83587124

Ladyman, James, “Structural Realism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/structural-realism/>.

Romani, Gian Luca, Samuel J. Williamson, and Lloyd Kaufman. “Tonotopic organization of the human auditory cortex.” Science 216.4552 (1982): 1339-1340.

Van Fraassen, Bas C. “Structure: Its shadow and substance.” The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 57.2 (2006): 275-307.

Worrall, John. “Structural realism: The best of both worlds?.” Dialectica 43.1‐2 (1989): 99-124.