This is a topic I will address in a few different parts because I am connecting some divergent yet similar ideas. I wrote a preface to this topic earlier this year, discussing Sir Roger Penrose’s first book The Emperor’s New Mind. In it, he doesn’t really discuss what he think consciousness is per se, but mentions that it doesn’t result from some kind of algorithm or procedure. This conclusion would have, at the time, differed from prevailing views of the mind. His second book does a better job at theorizing the causes of consciousness, which is what I will discuss here.

In Shadows of the Mind, Penrose’s general claim is that we probably need a new understanding or perspective of physics to understand what consciousness is and how it comes about. Though I am sympathetic and open-minded, I don’t think we necessarily need a new understanding of physics to draw some preliminary conclusions about consciousness. That said, there very well could be physical aspects of consciousness that are poorly understood, if at all. These are the ideas I would like to explore in this series of posts titled “A Quantum Theory of Consciousness.” Although I have a basic theory of consciousness, that doesn’t mean there isn’t more to the story.

Penrose begins Shadows with a discussion of minds and robots, a topic I won’t discuss here because my thesis has covered this topic in depth. There may be room to expand and elaborate on this topic, but I won’t do it in this post. In section 1.3, Penrose provides four options for thinking about consciousness, which he labels A through D:

A: All thinking is computation; in particular, feelings of conscious awareness are evoked merely by the carrying out of appropriate computations.

B: Awareness is a feature of the brain’s physical action; and whereas any physical action can be simulated computationally, computational simulation cannot by itself evoke awareness.

C: Appropriate physical action of the brain evokes awareness, but this physical action cannot even be properly simulated computationally.

D: Awareness cannot be explained by physical, computational, or any other scientific terms.

Though Penrose is interested in exploring option D, I am of the belief that C is the more appropriate view. In fact, I think Penrose makes a category error in his preference for D, as an explanation of consciousness which appeals to quantum mechanics is still explained by physical and scientific terms. It’s just that the terms and ideas he appeals to aren’t fully understood or generally accepted, however, they nonetheless comport with physics in general. We aren’t appealing to some spiritual cause here; instead, we are expanding what is meant by “physical” and “scientific.” Regardless, I don’t think it would be wise to deviate from C, as this would lead us back to something like conjecture or spiritualism. I mean we can, but then anything goes, and there’s no fun in that.

A few pages later, Penrose draws some interesting conclusions on simulations that I’d like to briefly touch on. He appeals to Searle to state that “a physical process is very different thing from the actual process itself. (A computer simulation of a hurricane, for example, is certainly no hurricane!)” Yes indeed, this a very important idea to keep in mind with respect to robots. As I argued in my thesis, the simulation of empathy does not mean that true empathy is present.

To his credit, Penrose does admit on page 15 that he believes that “C is the [option] which… [is] closest to the truth.” That said, since he and others do not have an idea of what C might involve, D is also worth exploring. This is just a clarification I needed to pointed out for the sake of charitability.

The rest of Chapter 1 and Part 1 explores some interesting and related topics, but I won’t go into them here because I’ve already discussed my opinions of these ideas in my thesis, or they veer into a tangent that isn’t all that important to my purpose here. What I will say is that in 1.7, Penrose discusses Chaos. This is a good thing, as he is approaching an important topic related to minds and complex systems in general. He claims that “the future behaviour of the system depends extremely critically upon the precise initial state of the system” but initial conditions aren’t the only aspects that matter. Every physical system necessarily interacts with other physical systems, and a multitude of variables are always present. Initial variables are important, but there could be other variables that might matter as well. Think about making a loaf of bread. The amount of yeast, salt, and sugar, as initial variables, are very important indeed. However, there could be other variables at play which do not exist in the beginning, like changes in temperature or humidity. The world around us is complex and ever-changing, and a number of variables which are not present in the initial stages will also impact the outcomes of complex systems. Random events occur which end up influencing the outcomes of systems which cannot be accounted for during the initial stages. You can be driving correctly, following the rules of the road and acting cautiously, when all of the sudden, out of nowhere, a vehicle from the oncoming lane swerves directly in front of you. There are always variables which cannot be fully accounted for. Later on, Penrose mentions that “the question of whether or not something can be simulated in practice [sic] is a separate one from the in principle [sic] issues that are under consideration here.”

As a quick aside, when Penrose states that something is “computational,” he means that it can be articulated through an algorithm or series of procedures to reach a conclusion or outcome. During the 20th century, it was thought that the mind worked like a computer, rather than the other way around. In actuality, the mind produced computers as a reflection of their own rational capacities. The cart was placed before the horse, so to speak. The mind is an outcome of physical systems which, eventually, in evolutionary timelines, gave rise to abstractions and algorithms. Once human brains became sufficiently advanced, they could produce procedures and processes which could be articulated as a series of steps. Otherwise, there is only “know-how” or the ability to just do something, like score a goal or make pierogies. Penrose, like countless others before and after him, make this error. One of these individuals is Yuval Noah Harari, and his book Homo Deus exemplifies this critical mistake. I am very much looking forward to writing a review of this book.

Before skipping ahead to the meat of Penrose’s argument, let’s quickly review why he is so interested in an alternate view of consciousness. He states in his first book The Emperor’s New Mind that the mind is not a computational thing because intuition and insight plays an important role in mathematical break-throughs, as seen in Gödel’s conclusions regarding the incompleteness of mathematics. In Shadows, he goes over this argument again to arrive at the idea that “human understanding cannot be an algorithmic activity” to which I, and anyone sympathetic to embodied cognition, will agree to. Instead, “meanings can only be communicated from person to person because each person is aware of similar internal experiences or feelings about things.”

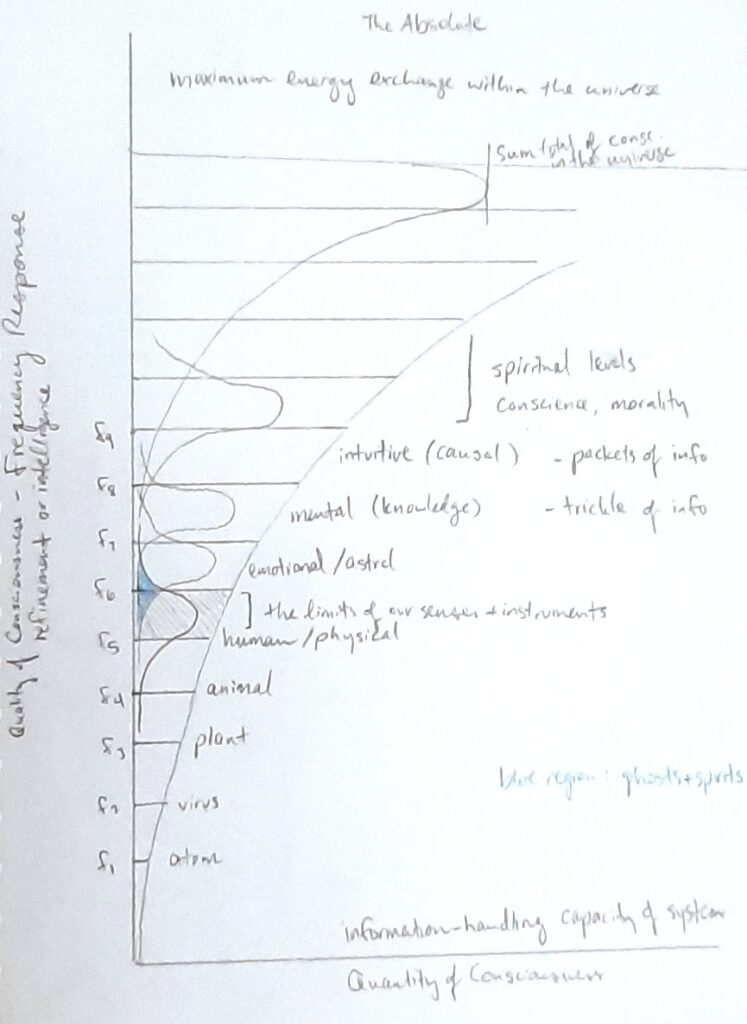

After much scrolling past discussions of Gödel’s contributions and resulting conclusions, we reach a discussion of what consciousness is. To be fair, Penrose takes the reader through a “quick” tour though quantum physics before connecting these theories to consciousness. He begins Chapter 7 with a reminder that neuronal activity exists as an “on or off” phenomena, where there are no alternatives which are characteristic of “quantum actions.” In quantum theory, it is feasible that some states may be both “on” and “off” at the same time with no contradiction. Moreover, quantum coherence refers to situation where a number of particles adhere to a single quantum state, namely “on” or “off,” which is decoupled or “unentangled” from the wider external environment. They seem to follow their own rules or patterns which remain independent from external factors.

In the fourth section of Chapter 7, Penrose introduces us to the “humble paramecium” with its “numerous tiny hairlike legs” called cilia. Paramecia are especially interesting because they are single-celled organisms which exist and thrive without nervous systems. Instead, they roam around governed by their cytoskeleton, the structure which secures their shape in addition to many more functions, like “transporting… molecules from one place to another.” Indeed, the cytoskeleton acts as a skeleton, muscles, circulatory system, and nervous system for the organism. The paramecium’s cilia are made up of microtubules, hollow cylindrical tubes which are arranged in fan-like structures when cut into cross-sections. Now, each microtubule is a protein polymer which can be divided into subunits called tubulins. Each tubulin consists of a dimer or pair of distinct parts, where each consists of about 450 amino acids. Together, these “peanut-shaped” protein pairs are arranged in different ways depending on their configuration and influenced by the presence of electrons. Messages can be propagated along the length of microtubules depending on the conformation of dimers, influencing the behaviour of these organisms. Given that neurons have their own cytoskeletons, Penrose speculates that neuronal activity is influenced by their microtubules, where the firing of neurons may have something to do with factors influencing their cytoskeletons.

How? Penrose appeals to studies conducted by Stuart Hameroff in the 1970’s which suggest that microtubules “might act as ‘dielectric waveguides.’ As such, the interior of the tube remains untangled with the environment for a certain amount of time, resulting in signals which can be passed to nearby microtubules. Is there evidence for this? Apparently so. When it comes to general anaesthetics, we do not have a robust understanding of how they work. In fact, a number of “completely different substances that seem to have no chemical relationship with one another” can render us unconsciousness. Nitrous oxide (N2O), ether (CH3CH2OCH2CH3), chloroform (CHCl3), and other chemical compounds, including the inert gas xenon, have anaesthetic effects on humans and animals. Penrose, following Hameroff’s work, suggests that these chemicals can interrupt microtubule functionality through their electric dipole properties. By changing the configuration of dimers which make up microtubules, the actions of microtubules can be influenced or interrupted. Penrose concludes that consciousness thus must rely on a functioning cytoskeleton, where factors which interrupt this functionality will influence consciousness in some way.

Therefore, the “mind is a mere shadow [sic] of the deeper level of cytoskeletal action–and it is at this deeper level where we must keep the physical basis of mind!”

Very interesting indeed, given that we still do not understand how general anaesthetics work. Perhaps there is some quantum phenomena at play to even render sensation and perception possible in the first place. There are likely layers of “awareness” which are necessary for high-level consciousness to manifest in mammals like humans.

Penrose concludes Shadows with a discussion of artificial intelligence and minds generally, stating that computational systems will never be able to “directly ‘feel’ things”. Since there is no understanding in computers, certain aspects of the world like beauty, goodness, and morality are beyond their comprehension. Truth, according to Penrose, is another aspect which is cannot be understood by computers, given the conclusions drawn by Gödel. Truth is a conclusion which can only be reached by minds, and not by algorithms or calculations. There must be an external system which can look inside a narrower system to determine whether some proposition is true with respect to the bigger picture. Statements and premises refer to a specific set of physical phenomena which can be represented formally, reducing the physical system to a formula which can be expressed in some kind of notation. Ultimately, “human insight lies beyond formal argument and beyond computable procedures.” Although Penrose goes on to state that this argues for the existence of the Platonic mathematical world, I won’t weigh in on that here, although I believe that I agree with him. “Mathematical truth is not determined arbitrarily by the rules of some ‘manmade’ formal system, but has an absolute nature, and lies beyond any such system of system of specifiable rules.” Yes, but in Emperor’s New Mind, Penrose states that algorithms are a part of this Platonic realm, which I disagree with for reasons I mentioned above. Minds create algorithms which are predicated on mathematical, Platonic truths, but without minds, there are no algorithms. Procedures belong to the physical world, because the interpreter needs a process whereby an outcome can be reached. The details of this process are determined by the ways in which the physical world operates.

So what now? Although sensation and perception appears to be dictated by the nervous system and the body, perhaps there is a realm of causality that influences how the body operates. Maybe some aspect of the physical world influences the firing of neurons, where the ideas and feelings we have are governed by forces we do not yet understand. I don’t know, this is why I am interested in this crazy stuff. I know that when I smell the lilacs I experience that wonderful, familiar scent, but do lilacs need to be present to trigger that sensation? Can my unverbalized thoughts influence the ideas or feelings that manifest in others? I don’t know, maybe we are all connected in ways we have yet to understand. There is room for interpretation and theory which comports with mystery and discovery. Human hubris only shuts out possibility, and while I am not a fan of unguided speculation, it is brash to rule out possibilities which have not been adequately explored.

In the next entry, I will dive into Itzhak Bentov’s discussion of the quantum mind and the ways it apparently connects to the physical world. Since he offers no evidence for his theory, we will see whether these ideas are factual or salvageable, however, I think they are nevertheless worth exploring. Life is short and consciousness might be forever, so let’s go for it.

Thank you for your patience as I write these entries. I really appreciate it. Stay curious dear reader, I think the world is far more mysterious and interesting than what we have been taught in school.

Roger Penrose, Shadows of the Mind: A Search for the Missing Science of Consciousness (Oxford University Press, 1994).

Penrose, 15.

Penrose, 21.

Penrose, 21.

Penrose, 24.

Hubert L. Dreyfus, What Computers Still Can’t Do: A Critique of Artificial Reason (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1992), xi.

Penrose, Shadows of the Mind, 51.

Penrose, 53.

Penrose, 348.

Penrose, 351.

Penrose, 357.

Penrose, 358.

Penrose, 359.

Penrose, 366.

Penrose, 368.

Penrose, 369.

Penrose, 369.

Penrose, 370.

Penrose, 376.

Penrose, 399.

Penrose, 400.

Penrose, 418.

Penrose, 418.