The Integrated Information Theory (IIT) of Consciousness is a theory originally proposed by Giulio Tononi which has since been further developed by other researchers, including Christof Koch. It aims to explain why some physical processes generate subjective experiences while others do not, and why certain regions of the brain, like the neocortex, are associated with these experiences. Evidently, he appeals to information theory, a technical domain which uses mathematics to determine the amount of entropy or uncertainty within a process or system. Less uncertainty means more information, where complex systems like humans and animals contain more information than simpler systems like an ant or a camera. Relationships between information are generated from a “complex of elements” and when a number of relationships are established, we see greater amounts of integration. Tononi states “…to generate consciousness, a physical system must be able to discriminate among a large repertoire of states (information) and it must be unified; that is, it should be doing so as a single system, one that is not decomposable into a collection of causally independent parts (integration).” This measure of integration is symbolized by the Greek letter Φ (phi) because the line in the middle of the letter stands for ‘information’ and the circle around it indicates ‘integration’. More lines and circles!

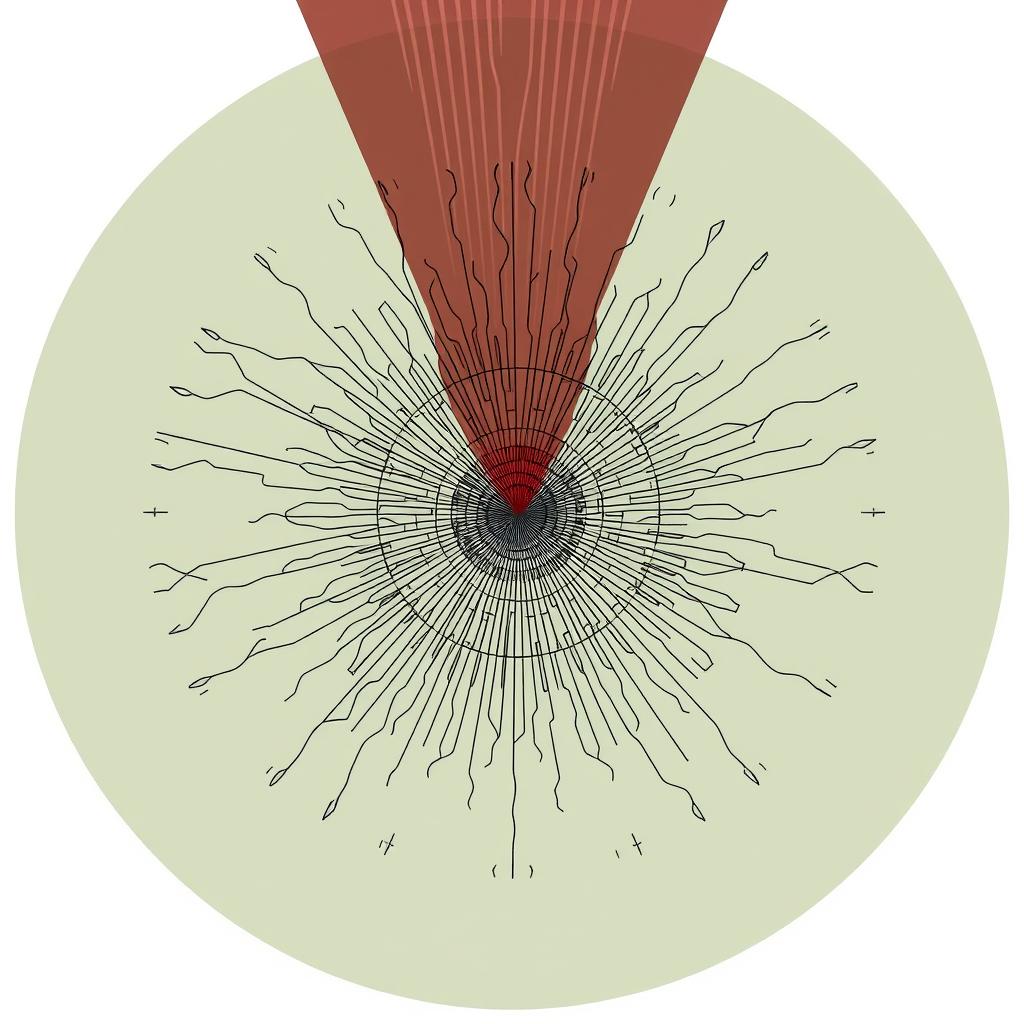

In addition to considering the quantity of information generated by the system, IIT also considers the quality of this information generated by its mechanisms. Both attributes determine the quality of an experience. This experience can be conceived of as a “shape” in a qualia space made up of elements and the connections between them. Each possible state of the system is considered an axis of the qualia space, each of which is associated with a probability of actually existing as that state. A particular quale consists of a shape in this state space, specifying the quality of an experience. Therefore, viewing a red object results in a particular state and shape in the qualia space, a mathematical object supposedly representing neuronal activity. As such, Tononi claims that his theory provides a way to describe phenomenology in terms of mathematics. Sure, however, this doesn’t really explain much about consciousness or qualia, it just provides a mathematical description of it.

In later publications, he attempts to clarify this theory a bit further. Rather than appealing to activity in the brain, his theory “starts from the essential phenomenal properties of experience, or axioms, and infers postulates about the characteristics that are required of its physical substrate.” The reason is because subjective experiences exist intrinsically and are structured in terms of cause-and-effect in some physical substrate like a brain. Experiences, therefore, are identical to a conceptual structure, one expressible in mathematics. By starting from axioms, which are self-evident essential properties, IIT “translates them into the necessary and sufficient conditions” for the physical matter which gives rise to consciousness and experience.

Not satisfied? I hear ya barking, big dog. When I first heard about it, I was intrigued by the concept but was ultimately unimpressed because it doesn’t explain anything. What do we mean by ‘explain’? It’s one of those philosophically dense concepts to fully articulate, however, a dictionary definition can give us a vague idea. By ‘explain’, we mean some discussion which gives a reason or cause for something, demonstrating a “logical development or relationships of” the phenomenon in question, usually in terms of something else. For example, the reason it is sunny right now is because the present cloud coverage is insufficient for dampening the light coming from the sun. Here, ‘sunny’ is explained in terms of cloud coverage.

We are not alone in our dissatisfaction with IIT. On Sept. 16th 2023, Stephen Fleming et al. published a scathing article calling IIT pseudoscience. The reason is because IIT is “untestable, unscientific, ‘magicalist’, or a ‘departure from science as we know it’” because the theory can apply to many different systems, like plants and lab-generated organoids. They state that until the theory is empirically testable, the label of ‘pseudoscience’ should apply to prevent misleading the public. The implications of IIT can have real-world effects, shaping the minds of the public about which kinds of systems are conscious and which are not, for example, robots and AI chatbots.

One of the authors of this article would go on to publish a longer essay on the topic to a preprint server on Nov. 30th that same year. Keith Frankish reiterates the concerns of the original article and further explains the issues surrounding IIT. To summarize, the axiomatic method IIT employs is “an anomalous way of doing science” because the axioms are not founded on nor supported by observations. Instead, they appeal to introspection, an approach which has historically been dismissed or ridiculed by scientists because experiences cannot be externally verified.The introspective approach is one which belongs to the domain of philosophy, more akin to phenomenology than to science. Frankish grants that IIT could be a metaphysical theory, like panpsychism, but if this is the case, it is misleading to call it science. If IIT proponents insist that it is a science, well, then it becomes pseudoscience.

As a metaphysical theory, I’m of the opinion that it isn’t all that great. It doesn’t add anything to our understanding because the mathematical theory is rather complex and doesn’t provide a method for associating itself with scientific domains like neuroscience or evolutionary biology. It attempts to, however, it’s explanatorily unsatisfactory.

That said, the general idea of “integrated information” for consciousness isn’t exactly wrong. My perspective on consciousness, based on empirical data, is that consciousness is a property of organisms, not of brains. There are no neural correlates of consciousness because it emerges from the entire body as a self-organizing whole. It can be considered a Gestalt which arises from all of our sensory mechanisms and attentional processes for the sake of keeping the individual alive in dynamic environments. While the contents of subjective experience are private and unverifiable to others, that doesn’t make them any less real than the sun or gravity. They can be incorrect, as in the case of illusions and hallucinations, however, the experiences as experiences are very real to the subject experiencing them. They may not be derived from sense data portraying some element of the natural world, as in the cases of visual illusions, however, there is nonetheless some physical cause for them as experiences. For example, the bending of light creates a mirage; the ingestion of a substance with psychoactive effects creates hallucinations. The experiences are real, however, their referents may not exist as an aspect of the external world, and may just be an artifact of other neural or physiological processes.

I’ve been thinking about this for many years now, and since the articles calling IIT pseudoscience were published, have been thinking some more. Hence why I’m a bit “late to the game” on discussing it. Anyway, once I graduate from the PhD program, I’ll begin work on a book which explains my thoughts on consciousness in further detail, appealing to empirical evidence to back up my claims. I have written an extensive discussion on qualia, accompanied by a video, aiming to present a theory of subjective experiences from a perspective which takes scientific findings into consideration.

My sense is that, for a long time, our inability to resolve the issues surrounding qualia and consciousness was a product of academia. We’re so focused on specialization that the ability to incorporate findings and ideas from other domains is lost on many individuals, or is just not of interest to them. I hope we are slowly getting over this issue, especially with respect to consciousness, as philosophy of mind has a lot to learn from other domains like neuroscience, psychology, cognitive science, and evolutionary biology, just to name a few.

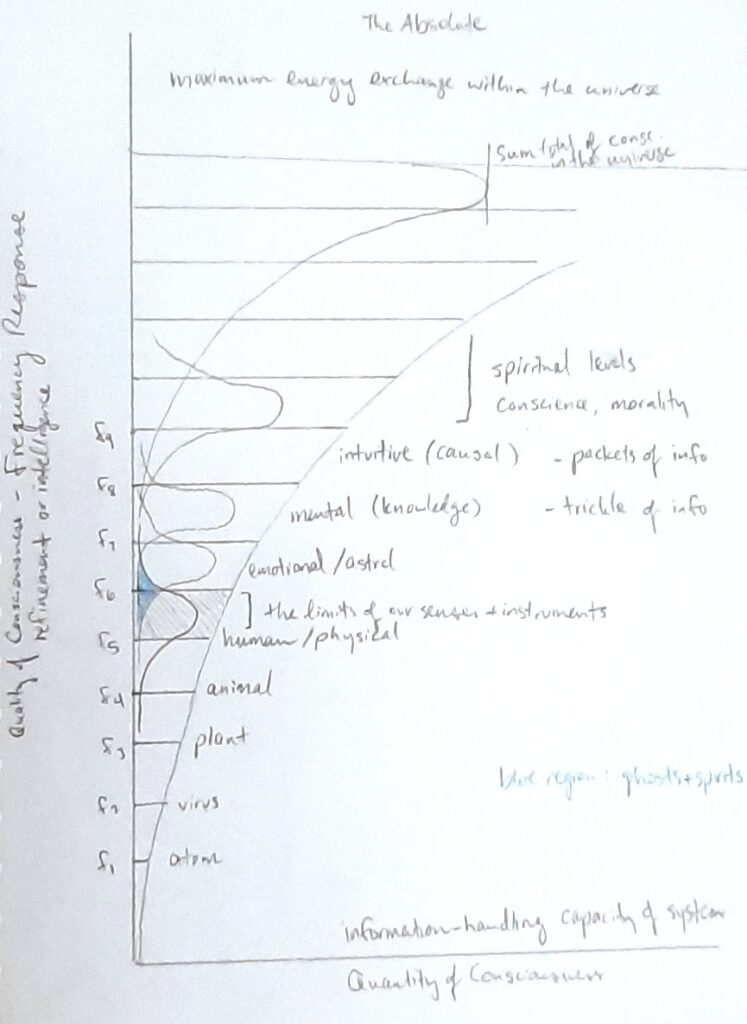

Consciousness is a property of organisms like humans and animals for detecting features of the environment. It comes in degrees; a sea sponge is minimally conscious, while a gecko is comparatively more aware of its surroundings. Many birds and mammals demonstrate a capacity for relatively high-level consciousness and thus intelligence. Obviously humans are at the top of this pyramid, given our mastery over aspects of our world as seen in our technological advancements. Consciousness, as an organismic-level property, emerges from the coordination and integration of various physiological subsystems, from systems of organs to specific organs and tissues, all the way down to cells and cellular organelles. It is explained by the interactions of these subsystems, however, cannot be causally reduced to them. Though the brain clearly plays an important role for consciousness and subjective experiences, it is a mistake to be looking for causal properties of consciousness in the brain, like a region or circuit. Consciousness is an emergent property of bodies embedded within a wider physical environment.

From this perspective, we can and have developed an analogue of consciousness for machines, as per the work of Dr. Pentti Haikonen. The good news is that because this machine doesn’t use a computer or software, you don’t need to worry about current AIs becoming conscious and “taking over the world” or outsmarting humans. It physically isn’t possible, and the recent discussions I’ve posted aim to articulate ontologically why this is the case. You ought to be far more afraid of people and companies, as explained by this excellent video from the YouTube channel Internet of Bugs.

Lastly, I want to extend a big Thank You to Dr. John Campbell for inspiring me to work on this explanation of consciousness, as per the helpful comment he left me on my qualia video. I recommend following Dr. Campbell on YouTube, he is a fantastic researcher and educator, in addition to being an honest, critically-thinking gentleman who covers many interesting topics related to healthcare.

Works Cited

Giulio Tononi, “Consciousness as Integrated Information: A Provisional Manifesto,” The Biological Bulletin 215, no. 3 (December 1, 2008): 216, https://doi.org/10.2307/25470707.

Tononi, 217; Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, Second (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1948), 17, https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11810.001.0001; C. E. Shannon, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” The Bell System Technical Journal 27, no. 3 (July 1948): 393, https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x.

Tononi, “Consciousness as Integrated Information,” 217.

Tononi, 219.

Tononi, 219.

Tononi, 220.

Tononi, 224.

Tononi, 228.

Tononi, 229.

Giulio Tononi et al., “Integrated Information Theory: From Consciousness to Its Physical Substrate,” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 17, no. 7 (July 2016): 450, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.44.

Tononi et al., 452.

Tononi et al., 460.

“Explain,” in Merriam-Webster.Com Dictionary (Merriam-Webster), accessed August 10, 2024, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/explain.

Stephen Fleming et al., “The Integrated Information Theory of Consciousness as Pseudoscience” (PsyArXiv, September 16, 2023), https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/zsr78.

Fleming et al., 2.

Keith Frankish, “Integrated Information Theory: Pseudoscience or Appropriately Anomalous Science?” (OSF, November 30, 2023), 1–2, https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/uscwt.

Frankish, 5.

Pentti O Haikonen, Robot Brains: Circuits and Systems for Conscious Machines (John Wiley & Sons, 2007); Pentti O Haikonen, “Qualia and Conscious Machines,” International Journal of Machine Consciousness, April 6, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793843009000207; Pentti O Haikonen, Consciousness and Robot Sentience, vol. 2, Series on Machine Consciousness (World Scientific, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1142/8486.