With fewer courses this term, I’ve had a lot more time to work on the topic I’d like to pursue for my doctoral research, and as a result, have found the authors I need to start writing papers. This is very exciting because existing literature suggests we have a decent answer to the Chalmer’s Hard Problem, and from a nonreductive functionalist perspective, can fill in the metaphysical picture required for producing an account of phenomenal experiences (Feinberg and Mallatt; Solms; Tsou). This means we are justified in considering artificial consciousness as a serious possibility, enabling us to start discussions on what we should be doing about it. I’m currently working on papers that address the hard problem and qualia, arguing that information is the puzzle piece we are looking for.

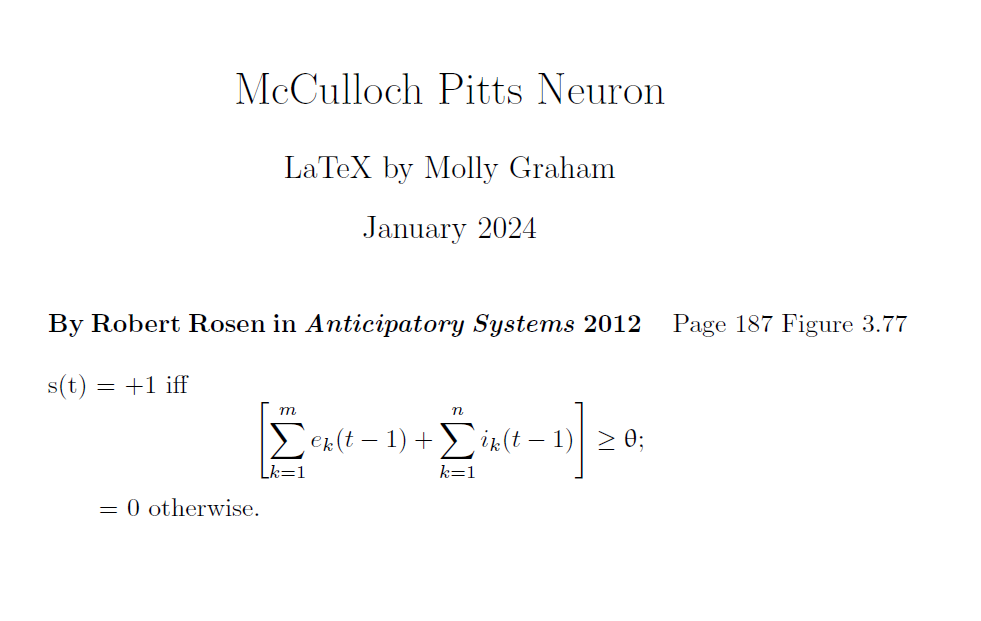

Individuals have suggested that consciousness is virtual, similarly to computer software running on hardware (Bruiger; Haikonen; Lehar; Orpwood) Using this idea, we can posit that social robots can become conscious like humans, as the functional architectures of both rely on incoming information to construct an understanding of things, people, and itself. My research contributes to this perspective by stressing the significance of social interactions for developing conscious machines. Much of the engineering and philosophical literature focuses on internal architectures for cognition, but what seems to be missing is just how crucial other people are for the development of conscious minds. Preprocessed information in the form of knowledge is crucial for creating minds, as seen in developmental psychology literature. Children are taught labels for things they interact with, and by linguistically engaging with others about the world, they become able to express themselves as subjects with needs and desires. Therefore, meaning is generated for individuals by learning from others, contributing to the formation of conscious subjects.

Moreover, if we can discuss concepts from phenomenology in terms of the interplay of physiological functioning and information-processing, it seems reasonable to suggest that we have resolved the problems plaguing consciousness studies. Acting as an interface between first-person perspectives and a third-person perspective, information accounts for the contents, origins, and attributes of various conscious states. Though an exact mapping between disciplines may not be possible, some general ideas or common notions might be sufficiently explained by drawing connections between the two perspectives.

Works Cited

Bruiger, Dan. How the Brain Makes Up the Mind: A Heuristic Approach to the Hard Problem of Consciousness. June 2018.

Chalmers, David. ‘Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness’. Journal of Consciousness Studies, vol. 2, no. 3, Mar. 1995, pp. 200–19. ResearchGate, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195311105.003.0001.

Feinberg, Todd E., and Jon Mallatt. ‘Phenomenal Consciousness and Emergence: Eliminating the Explanatory Gap’. Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 11, Frontiers, 2020. Frontiers, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01041.

Haikonen, Pentti O. Consciousness and Robot Sentience. 2nd ed., vol. 04, WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2019. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1142/11404.

Lehar, Steven. The World in Your Head: A Gestalt View of the Mechanism of Conscious Experience. Lawrence Erlbaum, 2003.

Orpwood, Roger. ‘Information and the Origin of Qualia’. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, vol. 11, Frontiers, 2017, p. 22.

Solms, Mark. ‘A Neuropsychoanalytical Approach to the Hard Problem of Consciousness’. Journal of Integrative Neuroscience, vol. 13, no. 02, Imperial College Press, June 2014, pp. 173–85. worldscientific.com (Atypon), doi:10.1142/S0219635214400032.

Tsou, Jonathan Y. ‘Origins of the Qualitative Aspects of Consciousness: Evolutionary Answers to Chalmers’ Hard Problem’. Origins of Mind, edited by Liz Swan, Springer Netherlands, 2013, pp. 259–69. Springer Link, doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5419-5_13.