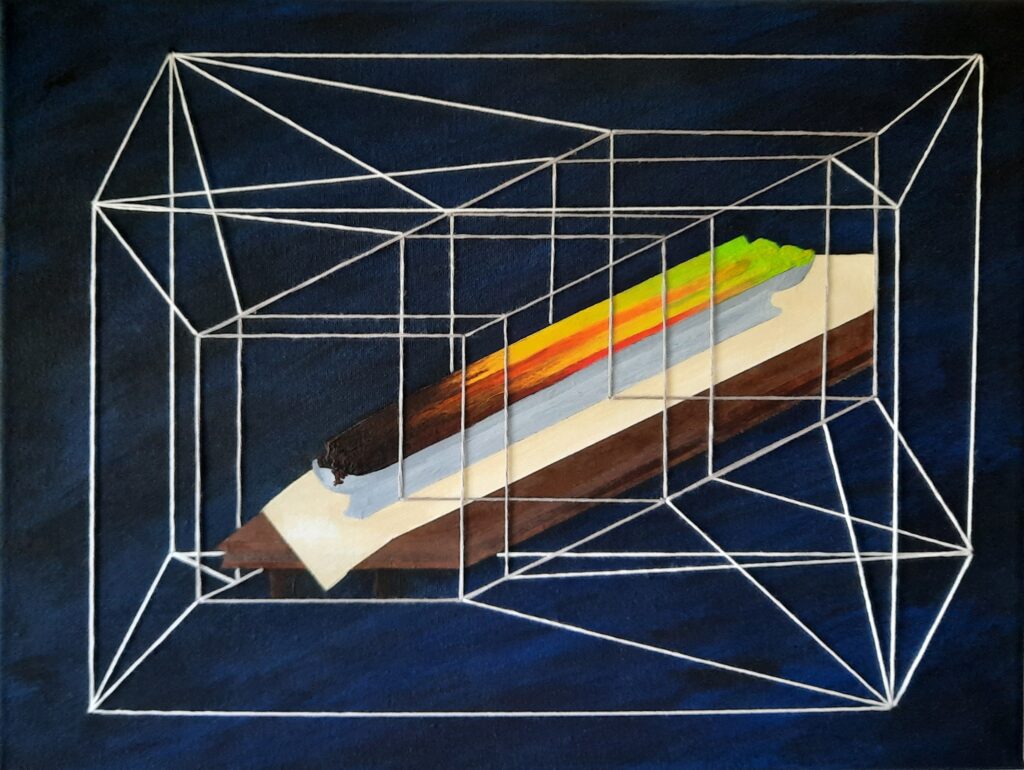

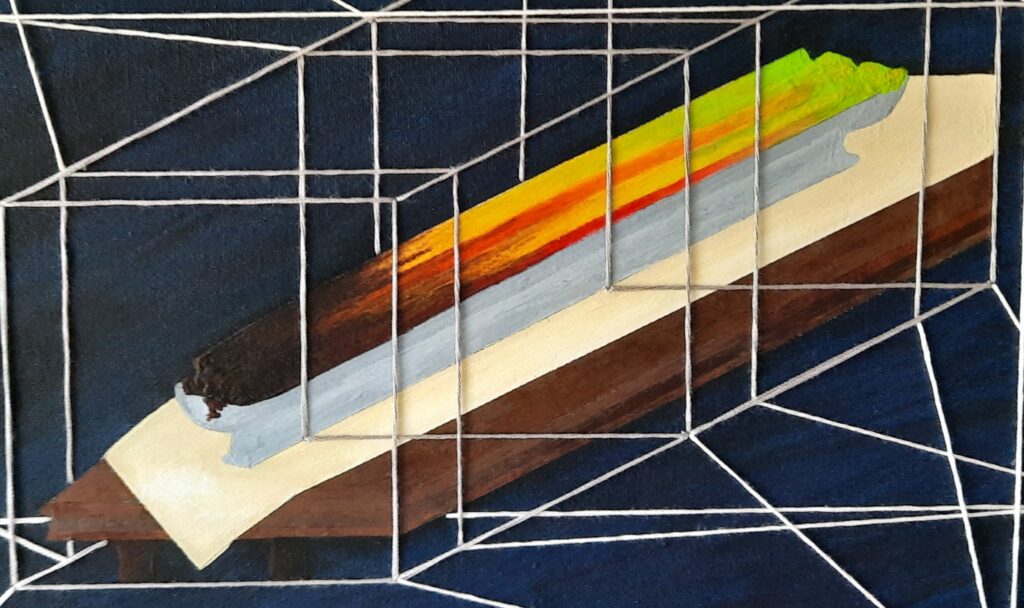

Still-life paintings from a new perspective: how does fruit ripen over time?

A depiction of a time lapse represented in 3 dimensions, from the perspective of 4 dimensions, on a mostly 2 dimensional plane.

Toward an empirical theory of consciousness for artificial intelligence

Frank Jackson’s famous thought experiment about qualia asks whether there are subjective facts about the colour red that are distinct from the physical facts produced through scientific inquiry (Jackson 291). The story involves an individual named Mary who grew up in a black-and-white room and has never seen any colours, but has studied everything there is to know about “redness” and how the brain processes light. As a neuroscientist, her studies have provided her with a robust theoretical understanding of colour perception without ever having experienced colour herself, leading us to wonder whether she learns anything new about the colour red after she sees red for the first time. The claim Jackson is interested in making is that there is no information about the experiences of others that Mary had not learned about while in her room. If Mary were to be released only to “realize how impoverished her conception of the mental life of others has been all along” Jackson suggests this generates a problem for physicalism (292).

William Lycan believes Mary would learn something new upon leaving the room because she is now presented with a new form of representation, namely, one produced by the act of introspection (Lycan 389). Building on Nagel’s ideas about what-it-is-like to experience things from a certain perspective, Lycan suggests the mind presents objects or features of the environment in a “special, uniquely internal point of view” (Lycan 390). More interestingly, Lycan goes on to suggest that the contents of these introspective representations are “non-physical pieces of information” (Lycan 391). This is because these internal representations are not synonymous with English words, or any other natural language words, because the internal monitors present within our bodies do not rely on linguistics. What I am assuming he means by this is that although we may use language for inner speech or verbalized thought, representations for qualia or phenomenal experiences such as redness or pain do not use language, but are intrinsic to the body and are relatively ineffable (Dennett 385). Lycan also suggests that these representations are non-physical because neuroscience is unable to provide information on introspective content, and as such, Mary could only represent other people’s experiences of red from a public, neuroscientific perspective (Lycan 393).

While this thought-experiment might pose problems for certain physicalist views, our general understanding of the world at this point in time can start to account for why Mary learns something new upon leaving the room. As she learns about how her own body generates experiences of red from a first-person perspective, she is now able to understand how others must use these internal representations as well. Since neuroscience is only interested in the functional organization of the brain and nervous system, Mary does not know how red appears to subjects engaging with particular wavelengths of light. Prior to her release, Mary could theoretically understand how individuals shop for tomatoes, but without the ability to see red, how this selection process is experienced from an individual’s perspective is still a mystery to her. The inner, subjective details of how people generally go about searching for the ideal tomato were previously off-limits, as her abilities to discriminate colours had yet to be developed. As such, Mary’s understanding of what redness means, especially when fruit shopping, would have been incomplete. Her own, internalized associative network of red objects and their commonalities would be absent or piecemeal, therefore limiting her understanding of how we collectively think about and interact with redness or red objects.

Works Cited

Dennett, Daniel C. ‘Quining Qualia’. Consciousness in Modern Science, Oxford University Press, 1988, pp. 381–414.

Jackson, Frank. ‘What Mary Didn’t Know’. The Journal of Philosophy, vol. 83, no. 5, JSTOR, 1986, pp. 291–95.

Lycan, William G. ‘Perspectival Representation and the Knowledge Argument’. Consciousness: New Philosophical Perspectives, OUP Oxford, 2003, p. 384.

With fewer courses this term, I’ve had a lot more time to work on the topic I’d like to pursue for my doctoral research, and as a result, have found the authors I need to start writing papers. This is very exciting because existing literature suggests we have a decent answer to the Chalmer’s Hard Problem, and from a nonreductive functionalist perspective, can fill in the metaphysical picture required for producing an account of phenomenal experiences (Feinberg and Mallatt; Solms; Tsou). This means we are justified in considering artificial consciousness as a serious possibility, enabling us to start discussions on what we should be doing about it. I’m currently working on papers that address the hard problem and qualia, arguing that information is the puzzle piece we are looking for.

Individuals have suggested that consciousness is virtual, similarly to computer software running on hardware (Bruiger; Haikonen; Lehar; Orpwood) Using this idea, we can posit that social robots can become conscious like humans, as the functional architectures of both rely on incoming information to construct an understanding of things, people, and itself. My research contributes to this perspective by stressing the significance of social interactions for developing conscious machines. Much of the engineering and philosophical literature focuses on internal architectures for cognition, but what seems to be missing is just how crucial other people are for the development of conscious minds. Preprocessed information in the form of knowledge is crucial for creating minds, as seen in developmental psychology literature. Children are taught labels for things they interact with, and by linguistically engaging with others about the world, they become able to express themselves as subjects with needs and desires. Therefore, meaning is generated for individuals by learning from others, contributing to the formation of conscious subjects.

Moreover, if we can discuss concepts from phenomenology in terms of the interplay of physiological functioning and information-processing, it seems reasonable to suggest that we have resolved the problems plaguing consciousness studies. Acting as an interface between first-person perspectives and a third-person perspective, information accounts for the contents, origins, and attributes of various conscious states. Though an exact mapping between disciplines may not be possible, some general ideas or common notions might be sufficiently explained by drawing connections between the two perspectives.

Works Cited

Bruiger, Dan. How the Brain Makes Up the Mind: A Heuristic Approach to the Hard Problem of Consciousness. June 2018.

Chalmers, David. ‘Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness’. Journal of Consciousness Studies, vol. 2, no. 3, Mar. 1995, pp. 200–19. ResearchGate, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195311105.003.0001.

Feinberg, Todd E., and Jon Mallatt. ‘Phenomenal Consciousness and Emergence: Eliminating the Explanatory Gap’. Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 11, Frontiers, 2020. Frontiers, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01041.

Haikonen, Pentti O. Consciousness and Robot Sentience. 2nd ed., vol. 04, WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2019. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1142/11404.

Lehar, Steven. The World in Your Head: A Gestalt View of the Mechanism of Conscious Experience. Lawrence Erlbaum, 2003.

Orpwood, Roger. ‘Information and the Origin of Qualia’. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, vol. 11, Frontiers, 2017, p. 22.

Solms, Mark. ‘A Neuropsychoanalytical Approach to the Hard Problem of Consciousness’. Journal of Integrative Neuroscience, vol. 13, no. 02, Imperial College Press, June 2014, pp. 173–85. worldscientific.com (Atypon), doi:10.1142/S0219635214400032.

Tsou, Jonathan Y. ‘Origins of the Qualitative Aspects of Consciousness: Evolutionary Answers to Chalmers’ Hard Problem’. Origins of Mind, edited by Liz Swan, Springer Netherlands, 2013, pp. 259–69. Springer Link, doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5419-5_13.

Can we build robots that act morally? Wallach and Allen’s book titled Moral Machines investigates a variety of approaches for creating artificial moral agents (AMAs) capable of making appropriate ethical decisions, one of which I find somewhat interesting. On page 34, they briefly mention “deontic logic” which is a version of modal logic that uses concepts of obligation and permission rather than necessity and possibility. This formal system is able derive conclusions about how one ought to act given certain conditions; for example, if one is permitted to perform some act α, then it follows that they are under no obligation to not do, or avoid doing, that act α. Problems arise, however, when agents are faced with conflicting obligations (McNamara). For example, if Bill sets an appointment for noon he is obligated to arrive at the appropriate time, and if Bill’s child were to suddenly have a medical emergency ten minutes prior, in that moment he would be faced with conflicting obligations. Though the right course of action may be fairly obvious in this case, the problem itself still requires some consideration before a decision can be reached. One way to approach this dilemma is to create a framework which is capable of overriding specific commitments if warranted by the situation. As such, John Horty’s Defaults with Priorities may be useful for developing AMAs as it enables the agent to adjust its behaviour based on contextual information.

Roughly speaking, a default rule can be considered similarly to a logical implication, where some antecedent A leads to some consequent B if A obtains. A fairly straightforward example of a default rule may suggest that if a robot detects an obstacle, it must retreat and reorient itself in an effort to avoid the obstruction. There may be cases, however, where this action is not ideal, suggesting the robot needs a way to dynamically switch behaviours based on the type of object it runs into. Horty’s approach suggests that by adding a defeating set with conflicting rules, the default implication can be essentially cancelled out and new conclusions can be derived about a scenario S (373). Unfortunately, the example Horty uses to demonstrate this move stipulates that Tweety bird is a penguin, and it seems the reason for this is merely to show how adding rules leads to the nullification of the default implication. I will attempt to capture the essence of Horty’s awkward example by replacing ‘Tweety’ with ‘Pingu’ as it saves the reader cognitive energy. Let’s suppose then that we can program a robot to conclude that, by default, birds fly (B→F). If the robot also knew that penguins are birds which do not fly (P→B ˄ P→¬F), it would be able to determine that Pingu is a bird that does not fly based on the defeating set. According to Horty, this process can be considered similarly to acts of justification where individuals provide reasons for their beliefs, an idea I thought would be pertinent for AMAs. Operational constraints aside, systems could provide log files detailing the rules and information used when making decisions surrounding some situation S. Moreover, rather than hard-coding rules and information, machine learning may be able to provide the algorithm with the inferences it needs to respond appropriately to environmental stimuli. Using simpler examples than categories of birds and their attributes, it seems feasible that we could test this approach to determine whether it may be useful for building AMAs one day.

Now, I have a feeling that this approach is neither special nor unique within logic and computer science more generally, but for some reason the thought of framing robot actions from the perspective of deontic logic seems like it might be useful somehow. Maybe it’s due to the way deontic terminology is applied to modal logic, acting like an interface between moral theory and computer code. I just found the connection to be thought-provoking, and after reading Horty’s paper, began wondering whether approaches like these may be useful for developing systems that are capable of justifying their actions by listing the reasons used within the decision-making process.

Works Cited

Horty, John. “Defaults with priorities.” Journal of Philosophical Logic 36.4 (2007): 367-413.

McNamara, Paul, “Deontic Logic”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2019/entries/logic-deontic/>.

I recognize this post will seem a bit tin-foily but I think it’s time we start acknowledging the consequences of a disrupted global supply chain. Perhaps things won’t get as bad as I am predicting but I think the underlying message will be relevant at some point. Ultimately, the standard of living we grew up taking for granted is about to change to some degree.

The majority of foods we consume and enjoy are dependent on global industries which are currently altering production and transportation protocols as demand and supply continue to change. Regardless of whether shortages arise due to nations restricting exports or locusts ravaging farmlands, it seems likely that by midsummer we will lose access to a variety of foods. Today, we see restaurants only offering take-away or delivery options in an attempt to find a balance between remaining open and upholding distancing measures. Grocery stores are either running out of products or limiting which items they order, as I hear shelves tend to be more empty these days. Before long, the service workers who prepare this food are likely to disappear too, as they themselves become sick or simply refuse to continue to put themselves at risk. Facilities where ready-made meals are prepared may also see a shortage of workers, limiting options for those who do not prepare their own food. We will be required to make everything ourselves, and before you call my a whiny millenial, remember that this is just the beginning. Processed foods will be next, including frozen meals, baked goods, canned soups and sauces, cookies, chips, crackers; anything that is not considered an ingredient. Eventually, however, personnel involved with all levels of the supply chain will be impacted in some way, leading to shortages of produce, dairy, and meat. I have been working on this post for a few weeks, and recently the talk of meat shortages has only increased. While we may not see wide-scale shortages until the end of the year, the decline in numbers of human workers is approaching and it will impact access to most foods.

While you may be able to survive a year without a decent burrito, these effects are not short-term as the entire world is in the midst of readjusting. You may have heard the stories of vegetables rotting in the fields or milk being dumped, but what you may not realize is these were ingredients for future foods too. The downstream effects will be a reduction in selection, and by selection I’m not talking about brands but categorical options. The only milk you may have access to is homogenized milk and cream; no skim, no 2%, and certainly no 1%. If you’re lactose intolerant, you may only be able to buy soy beverage given the recent nature of the American agricultural economy. Unilever or Kraft may have to cut production of certain items given these shortages, and suddenly we are in the midst of a type of food shortage in a time where emotional eating is at its height.

When you no longer have access to the things you love, the things that comfort you, what will you do? There are other forms of escapism and sugar comes in many forms, but we take variety for granted. We have become dependent on satisfying our appetites to some degree, regardless of whether it’s through alcohol, sugar, fat, or caffeine. We cope by consuming these substances and take pleasure in their effects, but there may also be other associations with these foods which contributes to societal well-being. Families and mealtimes go hand-in-hand all over the world, and it is difficult to determine how changes to supply chains will impact social relations.

Another option for coping is through various forms of media, as it entertains us and distracts our minds from the horror of reality. The problem arises from the tight coupling of food and visual media, irrespective of advertising. Since food is a cultural activity enabled by peak globalism, and a source of human happiness, we may suffer if this shared experience has been diminished to some degree. This may become especially apparent if images of our favourite foods are continuously popping up in our attempts to distract ourselves. Currently, social media posts include pictures of homemade creations or recommended recipes, and scrolling through staged photos may enrage us if we can’t have what we are seeing. It will remind us of a time when we had it all but didn’t even know it.

Until then, we will begin to value normalcy as type of currency, where our motivations aim to meet a luxurious set of basic needs. First-world lifestyles are built on options and variety in the things we consume, from Netflix shows to vegetarian alternatives. Notions of scarcity in a postmodern society seem ironic because it implies a reduction in standard of living, not necessarily a threat to survival. As we take our current way of life for granted, the more we put ourselves at cognitive and emotional risk. We have to acknowledge our personal dependency on this consumeristic environment we grew up assuming was normal. This has produced a level of entitlement which is about to be threatened or at least thrust into the spotlight, and perhaps leading to a reduction in emotional well-being. Some are frustrated by the actions of those who believe their freedoms are being restricted, and those protesting lock down orders inspire others to demand things “return to normal.” I don’t see it happening. Will this lead to societal unrest, especially as unemployment numbers grow? Of course it’s difficult to determine how society will adjust to this new normal, but I don’t like the way things are going today. Throw a change of available coping mechanisms into the mix and ask yourself, how are we going to handle this adjustment to a new normal? Maybe we won’t feel it until this time next year, but I believe our collective emotional well-being is about to deteriorate, for a number of reasons.

When learning about theatre back in high school, my drama teacher mentioned comedy arises from two basic principles:

1. It’s funny because it’s not me

2. It’s funny because it’s true

This has probably been said at one point, but I would like to offer a third principle for consideration:

3. It’s funny because it’s me

Why is this different than the second principle? While there may be some overlap, we often think of ourselves as separate from typical functions which determine truth values. Sure, we are able to run through a list of propositions about ourselves and can evaluate them like any other, but there is something more at play here.

Sometimes our feelings hint at things we aren’t ready to confront. Are you able to look yourself in the mirror and say “it is true that I am ___?” Maybe for certain characteristics this is easy, but others may be more difficult to admit. Our laughter, however, suggests we have understood some property about the world, and may be able to relate it to other things, perhaps to ourselves and others, in ways that are less explicit or unarticulated. We may feel amused for several reasons, one of which may include a certain level of meta-analysis. Perhaps deep down we are aware of one character trait we are not proud of but are able to recognize in a moment of leisure. This openness to information may allow ourselves to acknowledge aspects of our life or personality which we typically tend to hide or fix. Humour, especially reflexive humour, which turns the examination process back to oneself, can be therapeutic insofar as it allows us to understand ourselves without feeling the pressure to do anything about it. The first step to change is the recognition that something exists or must be better understood, and in this way, humour cracks the door to look at aspects of ourselves we wish to turn away from. The pleasure which accompanies laughter and humour allows us to relax and see through feelings of embarrassment or defensiveness.

Internet memes provide us with a way to laugh at ourselves and share our vulnerabilities with others. They serve as a reminder that we are human with troubles, flaws, and fears, but they also remind us that we are not alone. It’s easy to get wrapped up in our work, goals, and expectations as we compare ourselves with others and their accomplishments. As much as these aspects of life are important to some degree, we must always remember that the image others present to us is just a segment of their reality. Humour, especially when shared with others, reminds us to breathe; life is more than a to-do list of tasks.

There is a rich body of philosophical literature on humour that I have not yet had the pleasure of reading, but one day I will. As much as I would like to work on adding more to my Philosophy of Memes page, it’s a slow process because I should be focusing on school work! Until then, these considerations will be relatively uninformed and personal, and I look forward to rereading and laughing at my ramblings in 20 years from now.