This term I’m taking the course Science and Ethics, and this week we read Langdon Winner’s 1980 article “Do Artifacts have Politics?” along with a paper from 2016 published by Brent Daniel Mittelstadt and colleagues titled “The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate.” We are encouraged to do weekly responses, and considering the concerning nature of what these articles are discussing, thought it should be presented here. There is definitely a lot that could be expanded upon, which I might consider doing at a later time.

Overall, the two articles suggested risks of discriminatory outcomes are an aspect of technological advancements, especially when power imbalances are present or inherent. The paper The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate focused particularly on algorithmic design and its current lack of transparency (Mittelstadt 6). The authors mention how this is an epistemic concern, as developers are unable to determine how a decision is reached, which leads to normative problems. Algorithmic outcomes potentially generate discriminatory practices which may generalize and treat groups of people erroneously (Mittelstadt 5). Thus, given the elusive epistemic nature of current algorithmic design, individuals throughout the entire organization can truthfully claim ignorance of their own business practices. Some may take advantage of this fact. Today, corporations that manage to successfully integrate their software into the daily life of many millions of users have little incentive to change, due to shareholder desires for financial growth. Until the system which implicitly suggests companies can simply pay a fee, in the form of legal settlements outside of court, to act unethically, this problem is likely to continue to manifest. This indeed does not inspire confidence for the future of AI as we hand over our personal information to companies and governments (Mittelstadt 6).

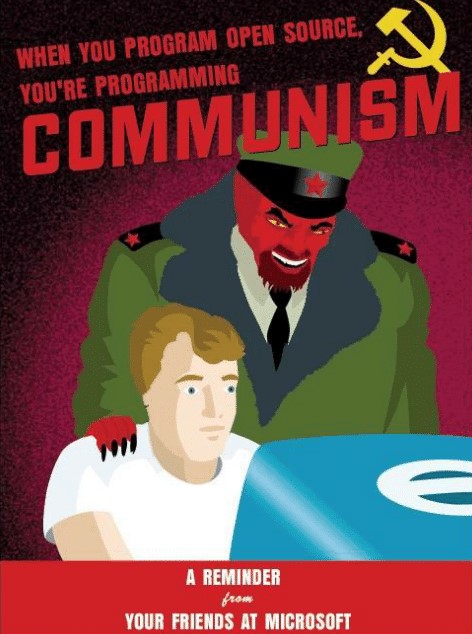

Langdon Winner’s on whether artifacts have politics provides a compelling argument for the inherently political nature of our technological objects. While this paper may have been published in 1980, its wisdom and relevance can be readily applied to contemporary contexts. Internet memes even pick up on this parallel; one example poses as a message from Microsoft stating those who program open-source software are communists. While roles of leadership are required for many projects or organizations (Winner 130), inherently political technologies have the hierarchy of social functioning as part of their conceptual foundations, according to Winner (133). The point the author aims to stress surrounds technological effects which impede social functioning (Winner 131), a direction we have yet to move away from considering the events leading up to and following the 2016 American presidential election. If we don’t strive for better epistemic and normative transparency, we will be met with authoritarian outcomes. As neural networks continue to creep into various sectors of society, like law, healthcare, and education, ensuring the protection of individual rights remains at risk.

Works Cited

Mittelstadt, Brent Daniel, et al. “The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate.” Big Data & Society 3.2 (2016): 1-21.

Winner, Langdon. “Do artifacts have politics?.” Daedalus 109.1 (1980): 121-36.